1960s black rock trailblazers Black Merda back with Fugi for a new album By Michael Jackman

October 21, 2016A trio of elderly musicians is gathered in the control room at Intimate Sounds recording studio on the west side of Detroit. But only the most engaged fan of the Motor City's psychedelic musical heritage would recognize them for what they are: yet another one of Detroit's ahead-of-their-time bands, long overlooked, only to be re-examined by fresh fans in a new century.

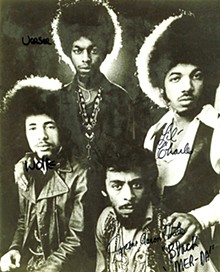

A generation ago, they emerged from a haze of fragrant marijuana smoke to become some of the baddest, most "psyched-out" musical trailblazers: Black Merda. The band — composed of brothers Anthony "Wolfe" and F.C. "Little Charles" Hawkins on guitars, VC L. Veasey on bass, and Tyrone Hite on drums — would go on to minor fame, releasing two LPs, and "Wolfe" and Veasey would join Edwin Starr's backing band.

Hite died in 2004, but the others live on, including the lanky vocalist who performed with them, Ellington "Fugi" Jordan, now on an extended visit with the band from Fresno, Calif., to record a new nine-track album and, they hope, to perform for crowds in the city where they made their best music together.

It's almost as if these guys never split up, the way they tease one another.

"Do you guys realize we're talking 48 damn years ago?" Fugi (pronounced FU-gee) asks. "Golly, man. We're so blessed to be doing something together again. We're old and ugly."

"Now you're talking about yourself," Veasy says, goading on Fugi with a smile.

"Naw, I'm talking about you two!" Fugi says, the others erupting in laughter.

Back in the late 1960s, these guys looked quite different from the relaxed seniors shooting the breeze today. As writer Fred Mills once described them forMetro Times, they were "all towering Afros, striped bell-bottoms, flashy shirts, and dangling scarves ... tighter and heavier than Parliament Funkadelic, and pursued by such Motor City heavyweights as Norman Whitfield and Eddie Kendricks."

In fact, Fugi pulls out a 12-year-old issue of Mojo Magazine that features a generous spread about the band, showing the wild threads and expansive naturals the band once wore. The article is one example of a renewed interest dating to the '00s in Detroit's little-known history of black rock, an interest that culminated in such cultural retrospectives as the film A Band Called Death.

In the last 15 years, much has been written about Black Merda. Suffice it to say that, in the early to mid-1960s, the musicians were part of a group called the Impact Band and Singers, players who'd perform covers at parties. Hite was a Detroit native, but the Hawkins brothers and Veasy had moved to the Motor City from the South and met in high school. They quickly gelled into a band, "just playing around the neighborhood," Veasy recalls.

They eventually solidified into a teenage session group for artists on small labels like Fortune and Golden World. "Somehow, word got around. They called us up and said, 'We want you to come play in the studio.'" The teenagers would back up an artist's demo, mostly for glory and fun, as the studio would hand them perhaps $10 or $15 a song. "It was cool money back then in the 1960s," Wolfe says.

The adolescent musicians were pulled out of their R&B trajectory after Veasy spent some time in the military and discovered Jimi Hendrix while stationed in the Pacific Northwest. The band quickly renamed itself the Soul Agents and adopted a psychedelic style, and even released the first known cover of "Purple Haze" in 1968. And, unlike the rest of Detroit's late 1960s acts, the Soul Agents didn't wear ties and blazers.

As Veasy puts it, "We was all dressed psyched-out" with Afros and denim, at a time when even Parliament was still wearing matching suits and slicked-down hair. "We didn't care what people thought about it," Veasy says. "People thought the way we dressed was cool, you know. ... We were so tight, we influenced George Clinton."

Enter Fugi

As music critics have become more excited about black rock, Black Merda is better known than ever. Less, however, has been written about the vocalist who created some unusual music with the band: Ellington Jordan, aka Fugi.

He grew up in Los Angeles, and was discovered by the Temptations at the Whisky a Go Go. The California native had just completed a seven-year prison sentence for stealing $11, and Temptation Eddie Kendricks decided that this young singer and songwriter needed to be brought to Detroit.

"I came here as a writer for Eddie Kendricks, and he put me up in his house," Fugi says. "He gave me a car and everything." Kendricks, who was often on the road with the Temptations at the time, left Fugi all alone, and Fugi says he spent his days goofing around the house.

"I just stayed high listening to 'Purple Haze' and stayed paranoid up in the house all the time because I didn't know what to do and where to go ... I used to go downstairs in the dressing room in his house and put on Temptations outfits, do the 'Temptations walk.' I used to go down there and act like I was a Temptation."

It wasn't long before Kendricks took Fugi down to a club on Puritan Street and introduced him to a band called the Soul Agents.

"I was so blown away by these cats and the style of music," Fugi recalls. "I had never heard nothing like that."

Watching the three men hang out in the studio, it's easy to get a sense of how Fugi fit into the scene. The longtime members of the Soul Agents were solid, stable friends by the time Fugi showed up. And then with Fugi's outgoing nature and pot-stirring energy, he provided a big personality almost built to react to. When this idea is raised with the group, Wolfe laughs and says, "Yeah, but it's exciting. It's never boring. That's the life-bringer."

Veasy says Kendricks "had a nice vision. He saw that we could work together."

Kendricks' intuition was bang-on. Soon, Fugi was practically living with the band in their house on Wisconsin Street near McNichols Road.

"I used to sit at the house," Fugi says, "and VC would be playing stuff on the acoustic. I would sit there and just look outside through the window, and I would go on a journey through his music because he gave me something to think about. He was able to take me spiritually and musically to another level."

And when it came to playing together, the hard-working backing band crafted a psychedelic sound that Fugi says fit him like a tailored suit of clothes.

"They actually created the style for me," Fugi says. "They gave me something I had never had in life, which was a musical identity."

The importance of that "musical identity" was impressed upon Fugi by head engineer Malcolm Chisholm at Chess Records, where Fugi had sat in and watched recording sessions in Studio C for such artists as Howling Wolf and Muddy Waters.

That studio is where Fugi and his new friends recorded the single "Mary Don't Take Me on No Bad Trip," released by Chess Records subsidiary Cadet. The track caught on in Detroit, signaling the changes to come for R&B.

"I was still running around with the Tempts," Fugi says, "and I was in the car with Melvin, Otis, and Eddie and I said, 'You guys think Motown would like this?' and they said, 'Hell no,' because it's too different. Right after that, they did Psychedelic Shack and I thought, 'You said my stuff wasn't good enough for you, but you put some the same kind of stuff out!"

By the time the psychedelic craze caught on in earnest, Chess was scrambling to get a Black Merda record out. But success was hard to find in the tumultuous music scene of the late '60s and early '70s. By the time 1970's Black Merda and 1972's Long Burn the Fire came out, the label was bought out and went in a different direction, and disco was ascendant in a quickly changing musical landscape.

But as Mills noted in his 2004 piece on the band, "while neither platter made any commercial impact, both went on to near-mythic afterlife in record-collector heaven."

The long way down

While Black Merda never hit the big time, Wolfe and Veasy did go on to a productive musical career backing Edwin Starr. What's more, they didn't face the same kinds of setbacks Fugi did after Merda's brush with stardom.

As Fugi makes clear, he was ill-prepared for the potholes in life's fast lane. He recalls the first morning he experienced withdrawal sickness: He woke up, ate a banana, and threw it back up right away.

"I was trying to figure out what the heck was wrong with me," Fugi recalls. "I'm sweating, and I was wet and hot and everything at the same time."

Disturbed by his sudden symptoms, he called bandmate Tyrone Hite and said, "Man, I sure feel bad. Feel like I got the flu."

"He said, 'You ain't got no flu, man. You hooked.' I said, 'Hooked on what?' He said, 'I'll be right over.' He brought me some drugs, right, and I got it, I sniffed it. Right away I started feeling fantastic. I knew then I was in trouble. I had a problem."

Dope sickness plagued Fugi as he traveled with the band, often playing congas on tour. He says he rode south most of the way to New Orleans sick on the floor in the back of the tour van, and when the band got to California, Fugi says, "I got hooked on dope again, and I just went off the set."

"I tried to do some things with Bobby Womack and some other people. We went to the Circle Star Theatre where Gladys Knight was performing in San Francisco, and went and knocked on the back door." Knight herself came and found Fugi, still hooked on drugs, and gave him $200, urging him to get himself together.

"I was riding with a few other cats," Fugi remembers, "and we said, 'F that,' and went and got some dope with that $200."

Eventually, his contract was sold to 20th Century Records, where, in 1972, Fugi recorded an album on the same label as Starr and Barry White. He says his album was scheduled to come out, and even had the art for the sleeve designed. Then a phone call shook him out of bed at noon one day: It was label executive Russ Regan on the line, saying, "Hey, Fugi. I gotta let you go." Fugi says he could barely ask why before Regan said, "Because, man, you introduced every secretary here to cocaine. Everybody in the damn company knows you're a drug addict, that you sell drugs. I just can't keep you here. You got a hell of an album, I wanna give you the opportunities. You come pick your tapes up, anytime you want."

Fugi picked up the tapes and held onto them, at least until he lost them through a drug deal.

"This guy I met, he talked me out of them. I needed some money for some dope, and he told me, 'I could take this tape and make some money for both of us.'" Fugi says. "I gave them to him, thinking he would put it out, and I never heard from him again. At the time, he gave me $500."

The onetime vocalist finally fell out of music altogether. Looking at his friends in the small studio, he tells them, "I didn't want to do no music. I didn't want to do nothing because I didn't have nobody to identify with. You guys were the closest thing to the music reality that I was up on."

Back on the block

Fugi remained mired in drug use for years, until 1980, when he says he kicked hard drugs for good — with a bit of supernatural help. He had called his family trying to speak to his mother. The voice on the line told him, "Man, we were looking for you. Your mom died two weeks ago and you missed the funeral and everything."

Fugi says what happened next he had a vision of his mother appear to him. "My mom visited me in spirit over myself," he says, "and she told me, 'I took care of everything for you. You ain't gonna want to use more drugs. You ain't gonna want to get hooked on no drugs.'"

"After that," he says, "I never wanted to use drugs again. And I've been clean 36 years: I never thought about using heroin or cocaine. I have never wanted to use that stuff."

For many of those years, he counseled groups on the hardships of drug abuse. These days, he says, he's even drifted away from smoking weed.

And, with the help of his wife, who he's been with for 30 years, he's finally come around to trying to reclaim what he lost so long ago. "I'm just praying and asking God to show me the way back, man. And this year, I just made up my mind: I told my wife, 'You know what? I'm going back to Detroit, getting back with the guys. Going to do some new stuff. Take some of our old stuff and put new arrangements on this music. Hopefully put some stuff together that we could identify with.'"

Fugi says, given Detroit's comeback narrative, he hopes the time is right for him to return to the people and places that gave him that brush with fame almost 50 years ago. And he wants the opportunity to perform for audiences of today, to make music, and to be reunited with the people who felt so much like family. Working with his old friends this month, he says, he has recorded "some of the best music in my life."

"Detroit had a glorious past," Fugi says. "Especially when you're talking about the kind of music that was produced here, with Motown, and some of the other big companies, writers, producers — we had everything going on here at one time. We want to create just like Motown did ... like it was in the past."

Posted by Black Merda. Posted In : Metro Times